Some Key Scientific Theories

- Eric Pappas

- Apr 5, 2019

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 9, 2019

Underlying the The Fast Change Project is a set of psychological theories that serve as a foundation for instruction and practice. This is a brief introduction to some of those theories.

Intentional Self-development

Intentional self-development (ISD) is the process of personal growth by which an individual

takes deliberate action to shape his/her own behavior, identity, and even personality. ISD can also be viewed more broadly as a cycle of self-regulation in which people perceive a personal need or goal, act, observe outcomes, and adjust accordingly. Central to ISD are personal goals, actions, concepts of self, and the interpretive processes through which the individual comes to generate and evaluate goals, actions, and selves (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002).

Bauer (2012) considers three preconditions under which individuals may change their own personality through self-directed efforts.

Individuals need to desire changing their behaviors either as an end in itself or in order to achieve other goals.

They need to consider behavioral changes feasible and be able to implement the desired changes.

Behavioral changes need to become habitual in order to constitute a stable trait.

Earlier, Zimmerman (1998) proposed a simpler tripartite model of ISD.

Forethought (setting a goal and deciding on goal strategies)

Performance control (employing goal-directed actions and monitoring performance)

Self-reflection (evaluating one’s goal progress and adjusting strategies to ensure success)

The Fast Change Project is an adventure in intentional self-development.

Resources:

Article: Intentional Self Development: A Relatively Ignored Construct

Article: A Three-Part Framework for Self-Regulated Personality Development across

Adulthood

Growth Mindset

According to Stanford Professor, Carol Dweck, Growth Mindset is the understanding that ability, intelligence, and character are not fixed and can be intentionally developed. Adopting a growth mindset has been linked to many positive outcomes (see graphic below).

Recent advances in neuroscience have shown us that the brain is far more malleable than we ever knew. Research on neuroplasticity has shown how connectivity between neurons can change with experience. With practice, neural networks grow new connections, strengthen existing ones, and build insulation that speeds the transmission of impulses. These neuroscientific discoveries have shown us that we can increase our neural growth by the intentional actions we take, such as using good strategies, asking questions, practicing, and changing habits. Recently, a series of interventions and studies demonstrate that we can indeed change a person’s mindset from fixed to growth, and when we do, it leads to increased motivation and achievement in a variety of contexts.

Resources:

Video: Growth Mindset vs. Fixed Mindset (2 minutes) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1CHPnZfFmU

Video: Growth Mindset vs. Fixed Mindset (5 minutes) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KUWn_TJTrnU

Video: Carol Dweck Developing a Growth Mindset with Carol Dweck

Video: Carol Dweck TED Talk The power of believing that you can improve | Carol Dweck

Self-determination Theory

Self-determination Theory (SDT) is a useful perspective on human motivation, emotion, and development that focuses on factors and behaviors that either facilitate or forestall an individual’s growth.

According to Deci and Ryan (1985), extrinsic motivation is a drive to behave in certain ways that comes from external sources and results in external rewards. Such sources include grading systems, employee evaluations, awards and accolades, and the respect and admiration of others. On the other hand, intrinsic motivation comes from within. There are internal drives that motivate us to behave in certain ways, including our core values, our interests, and our personal sense of morality. SDT also proposes three fundamental human needs that are typically satisfied by relatively high levels of intrinsic motivation: Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness.

While it may seem like intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are diametrically opposed—with intrinsic driving behavior toward our “ideal self” and extrinsic leading us to conform to the standards of others—there are other important distinctions between motivation types relevant to intentional self-development (Ryan & Deci, 2008).

Resources:

Video: What is Self determination Theory (2 min.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3sRBBNkSXpY

Video: Edward Deci - Self-Determination Theory https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m6fm1gt5YAM (8 min.)

Video: Motivation: What moves us, and why? (Self-Determination Theory)

Cognitive Dissonance

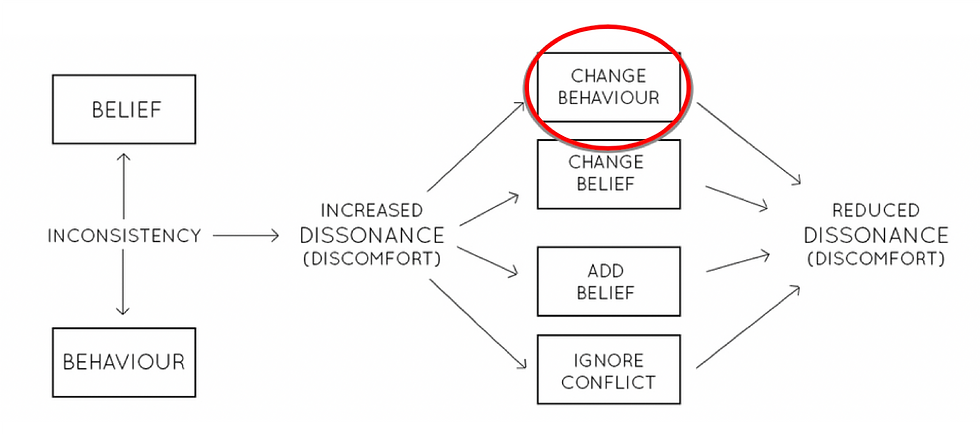

Our research has regularly used cognitive dissonance between stated values and observed behaviors as a catalyst for self-development and personal change (Pappas et al., 2018). Cognitive dissonance, first described by Leon Festinger (1957, 1962), is the feeling of mental discomfort that arises from having inconsistent thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes. Dissonance is also the result of realizing that one's behavior is in conflict with one's values. When this happens, one of several strategies is adopted to bring behavior and values into line (see graphic below).

Wicklund and Brehm (1976) explored how cognitive dissonance can be reduced by “changing the behavioral element” (p.5). We focus on this strategy as a motivator for both short- and long-term behavior change. Brehm and Cohen (1962) also noted that behavioral change was not only a central factor in reducing dissonance, but a necessary condition. Dissonance reduction in the form of active decisions or changed behaviors tends to persist, in some form or other, according to Wicklund and Brehm (1976), even years following the event, since maintaining such a cognitive state was not subject to continued motivation.

Resources:

Cognitive Dissonance: A Crash Course (7 minutes)

A Lesson in Cognitive Dissonance (5 minutes)

Cognitive Dissonance: Festinger’s Theory (3 minutes)

Immersion

As the term suggests, immersion is the state of being relatively consumed by some stimulus or action. It refers to a form of education in which an individual fully engages his/herself in a new habit or behavior they wish to change or acquire.

In some cases, immersive learning is used to describe certain experiences where an individual is placed in a new environment to develop or master a new skill…like short-term intensive training…or a course, like this one, focused on behavioral change. In particular, immersion creates an environment where individuals feel that they are fully present rather than distracted by thoughts and external stimuli.

According to David Boud (2008), “Immersion is a metaphorical term derived from the physical and emotional experience of being submerged in water. The expression, ‘being immersed in,’ is often used to describe a state of being which can have both negative consequences – being overwhelmed, engulfed, submerged or stretched, and positive consequences – being deeply absorbed or engaged in a situation or problem that results in mastery of a complex and demanding situation. Being immersed in a challenging experience might be uncomfortable but it is favorable for the development of insights, confidence and capabilities for learning to live and work with complexity” (p.9).

Immersive experiences are characterized by numerous effects that facilitate accelerated self-development, including:

Immersive experiences often relay a sense of personal change, growth, and gain.

Immersive situations often stimulate and require reflection and discovery of self.

People gain new insights on complex lives, and these insights may well connect with or change a person’s identity.

People in immersive situations often change their value systems and become more humble.

People become more self-aware and gain confidence in their own capability, often through the support of others and reflection leading to recognition of one’s ability. (Jackson & Campbell, 2014)

During week three (and to a lesser degree, week four) of The Fast Change Project, you will immerse yourself in your self-development goals.

Systems Theory

Systems Theory is the theoretical backdrop to Fast Change, a broad, integrative perspective that links elements of intentional self-development together and recognizes their interconnectedness. Based on your own experiences, you likely realize that almost nothing happens in isolation of other factors. For instance, a social change is likely to create emotional changes along with it. Emotional changes changes can affect health. Health impacts cognition (i.e. subjective well-being).

Everything is connected to something else, and a change in one context is likely to produce both predictable and unpredictable changes in the other contexts.

The systems-based contexts of Sustainable Personality engaged during The Fast Change Project include:

Cognitive

Emotional

Social

Physical

See the sustainable personality page for detail on each context.

Systems Theory finds some of its roots within the biological sciences, as some of the founders of its core concepts were biologists. One of the main perspectives of Systems Theory is viewing an individual or group as its own ecosystem with many moving parts that affect each other. Principles of Systems Theory have been applied to the field of psychology to explore and explain behavioral patterns (GoodTherapy.org).

Other definitions of Systems Theory:

Systems Theory, also called social systems theory, in social science, the study of society as a complex arrangement of elements, including individuals and their beliefs, as they relate to a whole (e.g., a country). The study of society as a social system has a long history in the social sciences. The conceptual origins of the approach are generally traced to the 19th century, particularly in the work of English sociologist and philosopher Herbert Spencer and French social scientist Émile Durkheim.

Systems Theory, also called systems science, is the multidisciplinary study of systems to investigate phenomena from a holistic approach. Systems, which can be natural or man-made and living or nonliving, are found in many aspects of human life. People who adhere to systems thinking, or the systemic perspective, believe it is impossible to truly understand a phenomenon by breaking it up into its basic components. They believe, rather, that a global perspective is necessary for comprehending the entire phenomenon.

References

Bauer, J. J. (2012). Intentional self-development. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.),

Encyclopedia of Positive Psychology. London: Blackwell

Boud, D. (2008). Locating Immersive Experience in Experiential Learning, Chapter 8 (Ebook)

Surrey Centre for Excellence in Professional Training and Education Conference University of Surrey, Guildford, January 2008

Brandtstädter, J., & Rothermund, K. (2002). Intentional self-development: Exploring the interfaces between development, intentionality, and the self. In L. J. Crockett (Ed.), Vol. 48 of the Nebraska symposium on motivation. Agency, motivation, and the life course (pp. 31-75). Lincoln, NE, US: University of Nebraska Press.

Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19( 2), 109-134.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 49(3), 182-185.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. California: Stanford University Press.

Festinger, L. (1962). "Cognitive dissonance." Scientific American. 207 (4), 93–107.

Jackson, N. & Campbell, S. (2014). Chapter D6: The Nature of Immersive Experience Learning to be Professional through a Higher Education e-book.

Pappas, E., Lynch, R., Pappas, J., & Chamberlin, M. (2018). Fast Change: Immersive Self-development Strategies for Everyday Life. Journal of Advances in Education Research, 3, 3.

Zimmerman, B. J. (1998). Developing self-fulfilling cycles of academic regulation: An analysis of exemplary instructional models. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Self-regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice (pp. 1-19). New York: Guilford Press.

© 2019 Eric Pappas, Jesse Pappas

Comments